The Atom

(a) Structure of the Atom

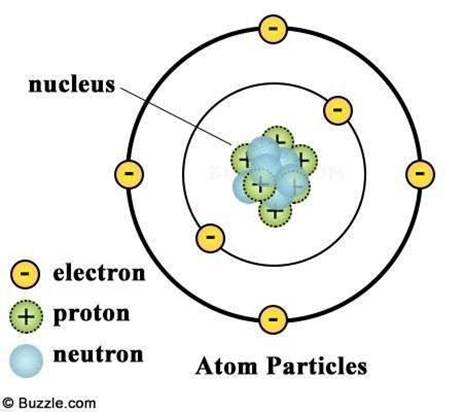

The atom is the basic unit of a chemical element. It consists of a dense central nucleus surrounded by a cloud of negatively charged electrons. The nucleus contains:

- Protons: Positively charged particles. The number of protons in an atom determines its atomic number (Z) and defines the element.

- Neutrons: Neutrally charged particles. The number of protons and neutrons together determines the mass number (A) of an atom.

- Dalton’s Atomic Model (Brief Review)

John Dalton proposed that all matter is made of tiny, indivisible particles called atoms. He suggested that atoms of the same element are identical and that chemical reactions involve the rearrangement of atoms.

- Rutherford’s Atomic Model

Ernest Rutherford’s gold foil experiment led to the discovery of the nucleus. He proposed that:

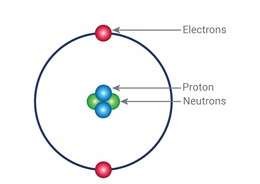

- The atom has a small, dense, positively charged nucleus at its center.

- Most of the atom is empty space.

- Electrons orbit the nucleus like planets around the sun.

A diagram illustrating Rutherford’s gold foil experiment with alpha particles being scattered by the nucleus. Another diagram showing the Rutherford atomic model with a central nucleus and orbiting electrons.

(iii) Atomic Number and Mass Number

- Atomic Number (Z): The number of protons in the nucleus of an atom. It uniquely identifies an element. For example, Hydrogen (H) has Z=1, Carbon (C) has Z=6.

- Mass Number (A): The total number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus of an atom. Number of neutrons = A – Z. For example, Carbon-12 has A=12 and Z=6, so it has 6 neutrons.

(b) Relative Atomic Mass of Elements

(i) Isotopes

Isotopes are atoms of the same element that have the same number of protons (same atomic number) but different numbers of neutrons (different mass numbers). For example, Carbon-12 (612C), Carbon-13 (613C), and Carbon-14 (614C) are isotopes of carbon.

A diagram showing the nuclei of the three isotopes of carbon, highlighting the different numbers of neutrons.

(ii) Relative Atomic Mass (RAM)

The relative atomic mass of an element is the weighted average of the masses of its naturally occurring isotopes, compared to 1/12th the mass of a carbon-12 atom. It takes into account the abundance of each isotope.

Formula for RAM:

RAM = [(% Abundance of Isotope 1 × Mass of Isotope 1) + (% Abundance of Isotope 2 × Mass of Isotope 2) + …] / 100

Example:

Chlorine exists as two common isotopes: Chlorine-35 (35Cl) with an abundance of 75.77% and a mass of 35 amu, and Chlorine-37 (37Cl) with an abundance of 24.23% and a mass of 37 amu.

RAM of Chlorine = [(75.77 × 35) + (24.23 × 37)] / 100 = [2651.95 + 896.51] / 100 = 3548.46 / 100 = 35.48 amu

(c) Electron Arrangement using s and p Notation

- Energy Levels and Orbitals

Electrons in an atom are arranged in specific energy levels or shells around the nucleus. These energy levels are further divided into sublevels called orbitals. Orbitals are regions of space where there is a high probability of finding an electron.

The first energy level (n=1) has one type of orbital called the s orbital. The second energy level (n=2) has two types of orbitals: one s orbital and three p orbitals. The third energy level (n=3) has s, p, and d orbitals, and so on. For the first 20 elements, we mainly focus on s and p orbitals.

- s orbital: Spherical in shape. Each s orbital can hold a maximum of 2 electrons.: A diagram showing the spherical shape of an s orbital.

- p orbitals: Dumbbell-shaped. There are three p orbitals in each energy level (except the first one), oriented along the x, y, and z axes (px, py, pz). Each p orbital can hold a maximum of 2 electrons, so a set of three p orbitals can hold a total of 6 electrons..

- Order of Filling Electrons (Aufbau Principle)

Electrons fill atomic orbitals in order of increasing energy. For the first 20 elements, the order of filling is approximately:

1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s

- Writing Electron Arrangement using s and p Notation

The electron arrangement (or electron configuration) shows how electrons are distributed among the orbitals in an atom. The notation indicates the principal energy level (n), the type of orbital (s or p), and the number of electrons in that orbital as a superscript.

Electron Arrangements of the First 20 Elements:

| Atomic Number (Z) | Element | Symbol | Electron Arrangement (s and p notation) |

| 1 | Hydrogen | H | 1s¹ |

| 2 | Helium | He | 1s² |

| 3 | Lithium | Li | 1s² 2s¹ |

| 4 | Beryllium | Be | 1s² 2s² |

| 5 | Boron | B | 1s² 2s² 2p¹ |

| 6 | Carbon | C | 1s² 2s² 2p² |

| 7 | Nitrogen | N | 1s² 2s² 2p³ |

| 8 | Oxygen | O | 1s² 2s² 2p⁴ |

| 9 | Fluorine | F | 1s² 2s² 2p⁵ |

| 10 | Neon | Ne | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ |

| 11 | Sodium | Na | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s¹ |

| 12 | Magnesium | Mg | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² |

| 13 | Aluminium | Al | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p¹ |

| 14 | Silicon | Si | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p² |

| 15 | Phosphorus | P | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p³ |

| 16 | Sulfur | S | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁴ |

| 17 | Chlorine | Cl | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁵ |

| 18 | Argon | Ar | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ |

| 19 | Potassium | K | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 4s¹ |

| 20 | Calcium | Ca | 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 4s² |

(d) Interest in the Study of Structure of the Atom

Understanding the structure of the atom is fundamental to comprehending how elements behave and interact to form molecules and compounds. This knowledge is crucial for advancements in various fields like medicine, materials science, and energy production. By exploring the subatomic world, we gain insights into the very nature of matter.

Activity Suggestion:

Watch a simulation of the Rutherford Gold Foil experiment and discuss the findings with peers to appreciate the scientific process of understanding atomic structure. You can also engage in simple activities to visualize the filling of electrons into orbitals using diagrams or models.

Sub-Strand 1.3: The Periodic Table

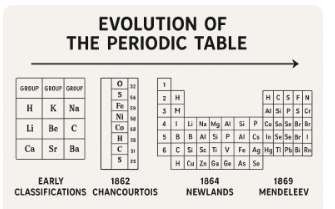

- Development of the Periodic Table

The periodic table is a systematic arrangement of chemical elements ordered by their atomic number, electron configuration, and recurring chemical properties.

- Early Attempts: Scientists like Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner with his “triads” and John Newlands with his “law of octaves” attempted to classify elements based on their properties and atomic masses.

- Mendeleev’s Periodic Table: Dmitri Mendeleev is widely credited with developing the first periodic table in 1869. He arranged elements in order of increasing atomic mass and noticed recurring patterns in their properties. He even predicted the existence and properties of undiscovered elements.

- Modern Periodic Table: The modern periodic table is arranged by increasing atomic number (number of protons), as discovered by Henry Moseley. This arrangement resolved some inconsistencies in Mendeleev’s table.

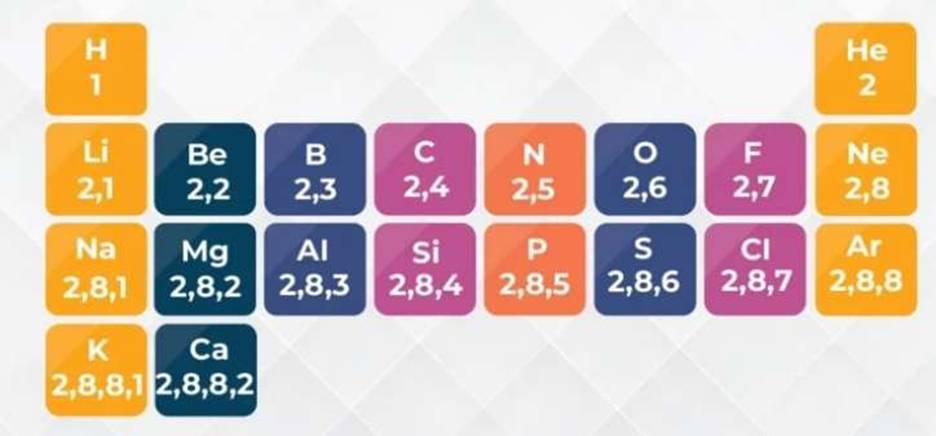

- Relating Position in the Periodic Table to Electron Arrangement

The position of an element in the periodic table directly correlates with its electron arrangement:

- Groups (Vertical Columns): Elements in the same group have the same number of valence electrons (electrons in the outermost energy level), which leads to similar chemical properties. The group number (for main group elements) often indicates the number of valence electrons.

- Example: Elements in Group 1 (Alkali Metals) have 1 valence electron (e.g., Sodium: 2, 8, 1 or 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s¹). Elements in Group 17 (Halogens) have 7 valence electrons (e.g., Chlorine: 2, 8, 7 or 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁵).

- Periods (Horizontal Rows): Elements in the same period have the same number of occupied electron shells. The period number corresponds to the highest principal energy level occupied by electrons.

- Example: Elements in Period 2 have electrons in the first and second energy levels (n=1 and n=2). Elements in Period 3 have electrons in the first, second, and third energy levels (n=1, n=2, and n=3).

- Ion Formation of Elements using the Periodic Table

Atoms tend to gain, lose, or share electrons to achieve a stable electron configuration, usually resembling that of the nearest noble gas (8 valence electrons, or 2 for Helium).

This process leads to the formation of ions:

- Cations (Positive Ions): Metals (generally located on the left side and in the middle of the periodic table) tend to lose electrons to achieve a stable configuration.

The charge of the cation is equal to the number of electrons lost.

- Elements in their elemental form have an oxidation number of 0 .

- The sum of oxidation numbers in a neutral compound is zero. For polyatomic ions, the sum equals the charge of the ion.

Deriving Valency and Oxidation Numbers from Electron Arrangement:

By looking at the electron arrangement, you can determine how many electrons an atom needs to gain, lose, or share to achieve stability, thus indicating its valency and likely oxidation states.

- Example: Oxygen (O) has an electron arrangement of 2, 6 (or 1s² 2s² 2p⁴). It needs to gain 2 electrons to achieve a stable octet, so its valency is often 2, and its oxidation number in many compounds is -2.

- Example: Aluminium (Al) has an electron arrangement of 2, 8, 3 (or 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p¹). It tends to lose 3 electrons to form Al$^{3+}$, so its valency is 3, and its oxidation number is +3.

- Deriving Formulae of Compounds

Chemical formulae represent the ratio of atoms of each element in a compound. We can derive them using valencies or oxidation states:

- Write the symbols of the elements involved.

- Write their valencies or oxidation numbers.

- Swap the valencies or oxidation numbers (ignoring the sign for valency).

- Simplify the ratio if possible.

Examples:

- Sodium Chloride: Sodium (Na) has a valency of 1, Chlorine (Cl) has a valency of 1. Swapping gives Na₁Cl₁, so the formula is NaCl.

- Magnesium Oxide: Magnesium (Mg) has a valency of 2, Oxygen (O) has a valency of 2. Swapping gives Mg₂O₂, simplifying the ratio gives MgO.

- Aluminium Oxide: Aluminium (Al) has a valency of 3, Oxygen (O) has a valency of

2. Swapping gives Al₂O₃, so the formula is Al₂O₃.

- Writing Balanced Chemical Equations for Simple Chemical Reactions

A balanced chemical equation represents a chemical reaction with the same number of atoms of each element on both the reactant and product sides.

- Write the unbalanced equation with the correct chemical formulae of reactants and products.

- Count the number of atoms of each element on both sides.

- Adjust the coefficients (numbers in front of the formulae) to balance the number of atoms of each element. Start with elements that appear in only one reactant and one product.

Example: Reaction between Magnesium and Oxygen to form Magnesium Oxide.

Unbalanced equation: Mg(s) + O₂(g) → MgO(s)

- Mg: 1 on left, 1 on right (Balanced)

- O: 2 on left, 1 on right (Unbalanced)

Balance Oxygen: Mg(s) + O₂(g) → 2MgO(s)

- Mg: 1 on left, 2 on right (Unbalanced)

- O: 2 on left, 2 on right (Balanced)

Balance Magnesium: 2Mg(s) + O₂(g) → 2MgO(s)

Balanced equation: 2Mg(s) + O₂(g) → 2MgO(s)

Suggestion: Examples of simple chemical reactions with corresponding balanced chemical equations, possibly with molecular models illustrating the rearrangement of atoms.

(h) Appreciation of Electron Arrangement in the Development of the Periodic Table

The periodic table is a testament to the fundamental role of electron arrangement in determining the chemical properties of elements. The recurring patterns observed in the periodic table directly reflect the periodic filling of electron shells and subshells. This understanding allows us to predict the behavior of elements and design new materials and technologies. The arrangement of elements based on their electron configurations provides a logical and powerful framework for studying chemistry.

Download more notes 2026 Grade 10 Notes Senior School Term1 2 and 3